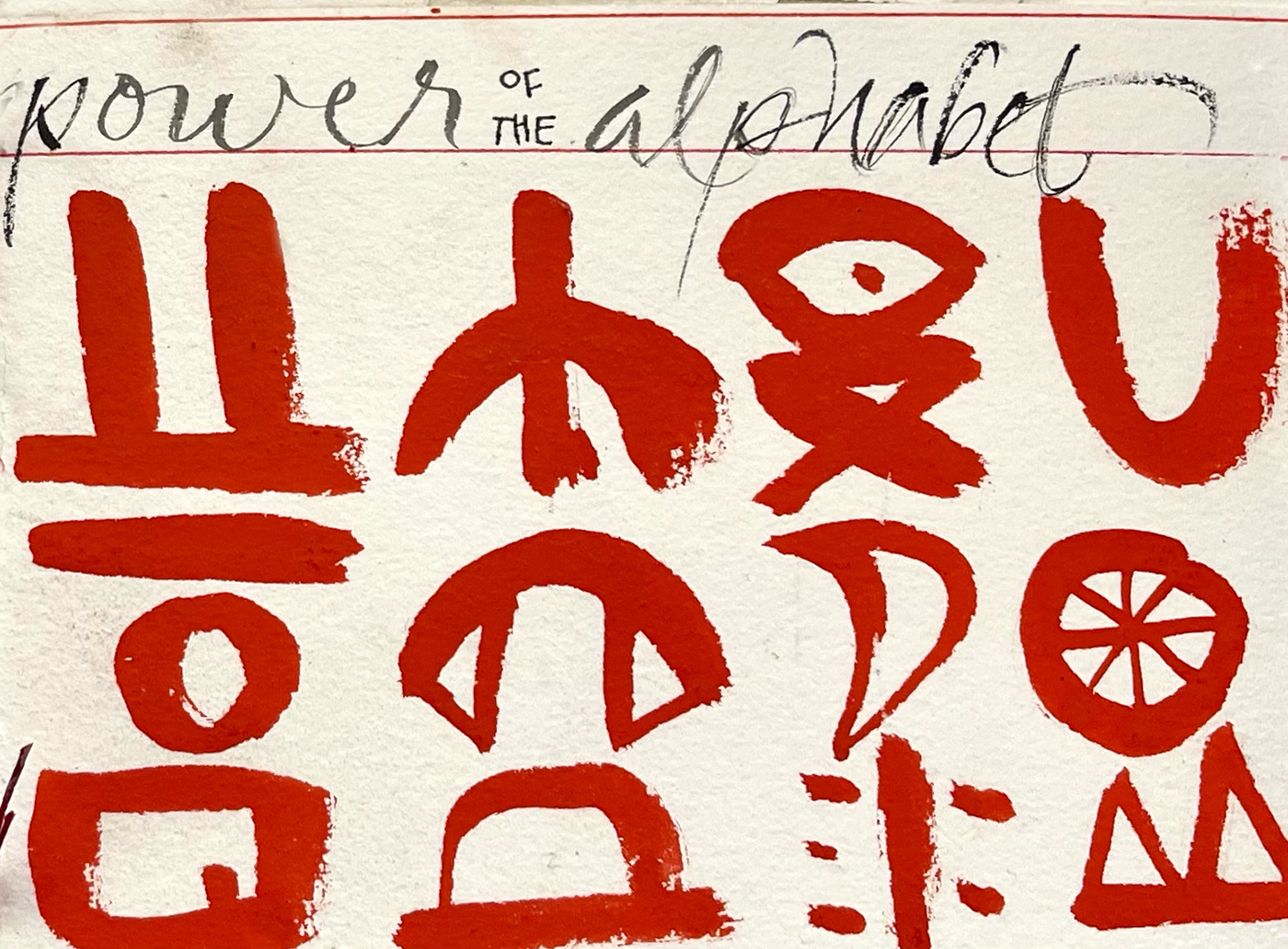

“Occult Power of the Alphabet”

In last month’s post, remake your world with words, we talked about the change-making potential of words and story. In this New Year’s post we will continue with this idea, sparked by another line from Gregory Orr’s poetry: the occult power of the alphabet. How can words, letters and stories become allies for hope and vision in this new year? Here is the first stanza of a much longer poem by Gregory Orr:

Occult power of the alphabet —

How it combines

And recombines into words

That resurrect the beloved

Every time.

The image of making words and recombining them, the feeling of resurrecting the beloved, stops me and fills me with desire to combine and recombine words. To feel the presence of the beloved. The last line of this stanza is only two words: every time. It resonates because this line is not folded into one compound word, but is two separate words with a pause in the middle. This vanquishes any doubt about the beloved returning. Now I am convinced that what the poem says is true; the alphabet, writing, has the power to resurrect the beloved every time — I only have to be willing to stay with it, to wait, to make myself an instrument, to be devoted to the time it takes.

The great wave is in waiting for any boat…

The worst is not to be overwhelmed by disaster, but to fail to live by principle.

— Sister Wendy Beckett

“Do you have hope for the future? Someone asked Robert Frost, toward the end. Yes, and even for the past, he replied”.

There is much more that can be said about Robert Frost’s hope for the future, and, in retrospect, the past. But for now consider that one way of re-kindling hope and perspective is to take a time apart from news and entertainment and open the wide door to imagination, the muse and uninterrupted time. Sometimes you have to go away from the world to enter more fully. Re-fueling and opening to what prompts us was our aim at the recent retreat in Taos, New Mexico. Time moves by another dial and is expanded by all the cross-pollination of ideas in the room. The work that comes has the aliveness of something discovered along the way.

“…creator and receiver both, work in alliance with the works…”

Greetings to all new and returning readers.

Welcome to “A Silver Fraction”* —

a place for makers, writers, thinkers

& anyone who wishes

to leave an imprint, make a mark, inscribe,

write, sing, perform, or paint;

to anyone who wants to make an offering,

no matter how small,

to this world we were given.

William Wordsworth’s epic poem, Prelude begins with an invocation to the muse: O welcome messenger! O welcome friend! A captive greets thee, coming from a house of bondage… Wordsworth, like most of us who struggle with what we make, calls out as an inmate wanting to free himself from prison. He activates the muse through his writing, through his willingness to beseech and make transparent his longing. Muse embodies the sense of the invisible otherness that is not you or me — but happens when “…creator and receiver both, work in alliance with the works…” When the creator and receiver are working together there arises a third thing; something in addition to you and your work; a presence in the room. Modern artists of all kinds summon the muse, a name for this unseen presence, a name given to us by the ancient Greeks. What we make is only a testimony to a greater desire to enter this mysterious province. What we make is only a testimony to a greater desire to enter this mysterious province. We need, now, more than ever, the comfort of being still long enough to feel this presence. What follows are some thoughts on invoking this presence with our hands.

“We are meant to know we have lived a life and not just done this and that.”

This time between Christmas and the New Year has always been a liminal time for me, a time to set down my ambition, my brushes and normal routine. I am reminded once again that awareness needs refreshing, that there is available all around us a source of wisdom and inspiration, if only we can limit the interference. How do I make myself more accessible to — what is your word — the muse, pure being, divine presence, the mystery, god? The something that is both inside us and otherness. Being a maker is my longing for this presence. I think it is what Rilke means when he says: Only in our doing can we grasp you. It is not so much about what we make as it is being an instrument that is ready for song. The instrument needs tuning. The vessel needs emptying. This is the hour of clearing and noticing signs. Yes there are the family and friend celebrations so integral and precious to this season, but the balance of time in silence is what prepares me for the new year. The openness to what wants to come leads me to a new focus for this threshold: listening, reading, walking and arranging.

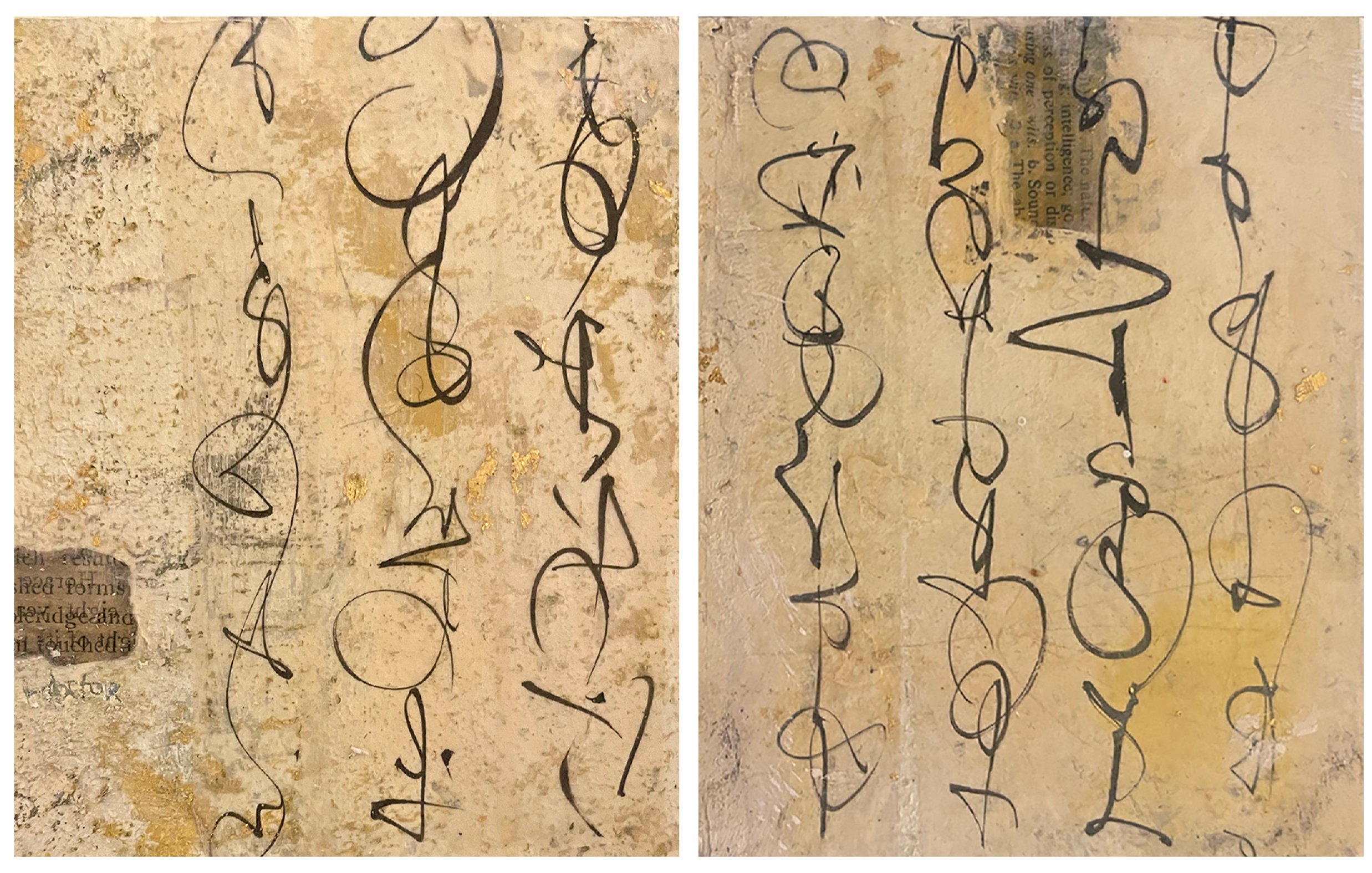

Experiments with “Calligraphic Still Life”

I promised in my last post to share ideas about these “calligraphic still lifes.” Many of you will have experimented with these tools, but perhaps not all together on the same surface, or as an exploration into still life. It’s only the beginning. I plan to go much further into abstraction, and into lettering and landscape. My aim is not to have products, but to play. This is working (I mean the part about playing.) My other aim is to have my students playing with tools they may not normally use, and to have tools that fit into my carry-on like crayons, oil pastels and watercolor. (I am sticking with my Mary Poppins effort to have all my clothes and tools and cosmetics for three weeks in Italy fit into one magic bag. At the moment I am in a room with art supplies, clothes, notebooks, journals, pen nibs, thread, soap, vitamin C and shampoo scattered across all surfaces.)

I made a couple short videos to share my process of experimenting with calligraphic still lifes:

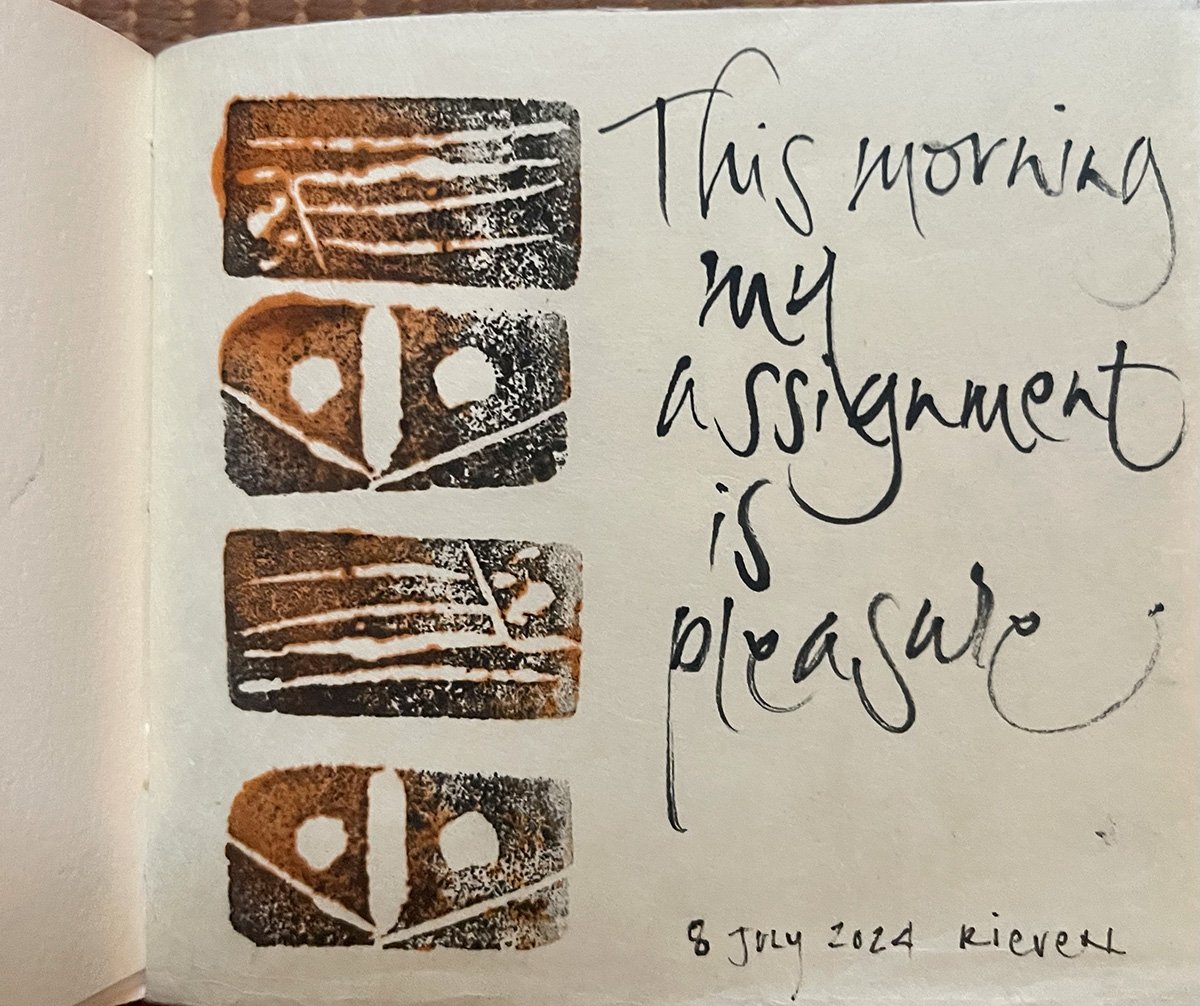

Maker is both a noun and a verb

“This morning my assignment is pleasure.” I wrote this in my sketchbook today as a remedy for the many hours I have spent agonizing over a painting, or a piece of writing, or one letter. The struggle is, in part, “the nature of the beast” — the uncertainty and self-doubt involved in the decision to be a maker, the conflict of leaping ahead instead of listening to what the work wants. The shift to plowing through any conceptual road blocks and doing something is a key. But the real guide for me is to work with some tool or surface or color that gives pleasure — even if what you are looking at, as I am now, is an immense pile of imperfect paintings or a tall stack of (mostly) unpublished writing.

Over and again I'm reminded of what I know, of what you know. I mean the most important kind of knowing, the kind that gets lost when I'm busy or distracted — for example, today, remembering when I take my small sketchbook with me, when I mark something down, even one small thing in a day — how this keeps me as a plant watered, rather than wilted. How this one mark can baptize everything that happens in a day.

“Cast upon yourselves a spell against stagnation.”

How is it that some of us go forward with vigor and adventure to the end, and some of us wither? Or, most likely, we have both qualities but wish to increase the former — the vitality that is connected to hope and self-confidence. How do we free ourselves from the mind-weeds and negativity that are obstacles to renewal? How do we cast a spell against stagnation?

The challenges will keep coming. Here in the desert, having time before class begins, I am making a list of things that are antidotes to ossification, the word itself reflecting the rigidity of bones. Here is my list so far:

Sit alone next to a tree, a place where you cannot be found except by the tree.

Turn left instead of right.

Reach out to someone you don’t like.

Stop thinking about your work and do it.

Stop thinking.

Make room for serendipity.

What follows is a week of serendipity and exploration in Taos, with wonderful images from the student work.

“Our summer made her light escape into the beautiful.” —

On this side of the world, outward-looking summer has ended just as spring is beginning in Australia. Wherever we are, we feel the shift of seasons and time passing. Here, the equinox, the balance of days and nights, is a reminder that even the happiest life requires balancing success and failure, glad and sad, right and wrong, pain and love. The movement into longer hours of darkness turns us inward. There is often a sense of loss when the long days of light recede. What is lost has the possibility of being returned to us in a new shape; a recognition of something deeper — seeds hidden in darkness.

Isn’t this what creation, the occupation of makers, is all about? Finding a new shape? Or recognition of a shape that is both new and has always been? In this short pause of equal days and nights, what is it that we wish to bring with us from summer into autumn? Or, on the other side of the world, what sleeping promise is ready for a new beginning?

“Turn me into song…”

How do you refresh your relationship with what is sacred?

The ancient idea of having a gatekeeper, a guardian for a sacred place, returns at a time when most gates have become porous to continuous interruptions — we are all “on call.” But without the stability of a gatekeeper that protects the threshold as barrier, the lightning-fast change that we are all a part of overruns its bounds, and transformation becomes a superficial commodity.

The kind of work that emerges when everyone agrees to protecting uninterrupted time is unpredictable, powerful, and often a breakthrough for the maker. This is what keeps me teaching — the delight that comes from doing work that you don’t already know how to do, from doing things that may be “ugly” or surprising or unexpected by taking the risk to be unavailable to anyone except the muse, by dipping into the Unknown.

What follows are some examples from the students in my recent class in San Francisco, a magnificent group. The work speaks for itself.

The creative act begins with planting one seed.

There’s a song sparrow that taps at our window every morning at dawn. Our window looks out over a ravine and gives the feeling of being in a tree house. The sparrow stands on the sill with his striped body tap-tapping at his own reflection — a would-be intruder in his territory and threat to his nest. I am struck by his diligence, as for over a month he has been tapping with his stout gray bill, going to all the windows on the north and west side of our house, facing an enemy in each one. I watch from the window as he flies away, wondering if he will reveal the hiding place for his nest, somewhere in the ravine.

Then I wonder how often we humans, with great diligence and sincerity, tap at imaginary dangers, fearing would-be enemies and what could happen next? How can we be ready for what comes, both the bad and the good, if we are tapping at our own reflection? It seems that many of us are still recovering from the isolation of Covid, from the despair of the world. And yet we know that tragedy, danger, and adversity are best met with a mind restored to clarity, to a condition of ease in spite of circumstance, and against all reason, a mind willing to welcome what comes.